AI and software production cycles: a paradigm shift

TL;DR

Generated by GPT for those who don’t have the time — or who can grasp everything at once 😄

AI doesn’t just change tools. It changes the economic rules of software. When producing software becomes much cheaper and much faster, production cycles, billing models and power dynamics inevitably shift. As with every major industrial disruption, most existing players will decline or disappear, a minority will adapt, and new entrants will capture a large share of the value. The real question isn’t whether AI will replace developers, but how to design, steer and sell software in a world where complexity and duration no longer hide inefficiency.

Throughout these lines, figures, examples and orders of magnitude are not intended as precise scientific measurements. They are field-based observations meant to highlight structural shifts and economic dynamics rather than exact metrics.

In a previous article, I argued that AI-related challenges depend heavily on the role you occupy.

This piece zooms in on one specific angle: software production cycles.

At a high level, AI impacts organizations along three main axes:

- internal processes (organization, management, HR), which is not covered here,

- software production cycles, the core focus of this article,

- AI as a feature embedded in products, which will be covered in a future article.

A paradigm shift in production cycles

When production cycles change, markets follow. And in the long run, there are always casualties.

You can’t fight this kind of shift. You can only prepare for it.

The current reality

Let’s be honest: a significant share of software projects never deliver the value initially expected.

This comes straight from the field: years of projects, discussions, and products that reached production… or quietly disappeared.

Ask yourself the same question, based on your own experience: “How many projects actually delivered what was originally planned?”, count those without:

- major pivots,

- partial abandonment,

- massive technical debt,

- being rewritten or shelved a few months later.

So… how many?

My intuition is that we’re probably not far from one project out of two ending up in heavy rework, abandonment, or as a product that never creates the expected value.

A brutal economic logic

When a company funds a software project, expectations are often surprisingly low.

In many cases, it is already considered a success if:

- the product reaches production,

- and roughly appears to address the original need.

From there, the logic is brutal.

Even if AI cannot produce a perfect product, if it can deliver something comparable at a cost 10 to 100 times lower, it becomes economically rational for decision-makers to seriously consider it.

The exact multiplier matters less than the scale shift itself: one large enough to radically alter economic trade-offs, decision-making processes and production cycles.

Another factor quickly comes into play: speed.

Producing faster also means failing faster. And failing faster avoids two- or three-year projects, extremely costly ones, that only reveal fundamental issues once everyone involved has already changed teams, roles or companies.

Shorter cycles surface problems earlier. They reduce sunk costs. They force decisions sooner.

This inevitably complicates commercial dynamics. Pricing models, commitments, accountability and risk-sharing all become harder to frame when production accelerates this much.

But complexity does not disappear.

It simply shifts.

A trivially common example: StopCovid / TousAntiCovid

Official visual of the StopCovid application, taken from a public communication by the French government

Official visual of the StopCovid application, taken from a public communication by the French government

The StopCovid / TousAntiCovid case is interesting not because it is exceptional, but because it is painfully common.

It also happens to be a French public-sector project, which makes the mechanisms unusually visible and relatively well documented.

According to publicly available information, several million euros were spent in just a few months on the initial StopCovid app before it was deeply reworked and replaced by TousAntiCovid. Initial development costs alone were around €9 million, with additional spending over time for operations, maintenance and successive iterations. Depending on what is included in the scope, total costs increased significantly beyond the first version.

At this point, the question is not whether there was corruption, favoritism in public tenders, or simple mismanagement. It was likely a mix of all of these, combined with urgency, complexity, and decisions made under pressure.

But that is not the core issue.

The real problem is structural.

Software projects are complex enough for responsibilities to blur, for decisions to remain defensible after the fact, and for overruns to become normalized. It often becomes impossible to clearly identify where things went wrong; or even to agree that something went wrong at all.

This opacity benefits everyone involved. Service providers bill. Intermediaries justify. Decision-makers move on. And the system keeps running.

StopCovid is just one illustration of a much broader pattern that extends far beyond public-sector projects.

What AI potentially disrupts is not only how software is produced, but the long-standing opacity between cost, effort and actual value delivered. When production becomes cheaper and faster, it becomes far harder to hide inefficiency, incompetence or abuse behind project complexity.

What AI really changes in software production cycles

The real question is not whether AI can replace developers by generating code. That debate is largely sterile technically, ethically, and strategically.

The real shift lies elsewhere.

In any industry, when you can produce the same type of deliverable, with comparable quality, at a much lower cost and often much faster, the outcome is almost always the same in a capitalist system: the lowest-cost production model eventually prevails.

Not because it is perfect. But because it is good enough.

This is not new. We have seen this mechanism play out repeatedly across very different industries.

What matters is not technical superiority, but a structural change in cost, speed and iteration capability. Once that threshold is crossed, economic pressure does the rest.

This is the kind of shift AI is introducing into software production cycles.

It does not eliminate complexity. It compresses time. And by doing so, it exposes inefficiencies that were previously hidden behind long timelines and high costs.

A familiar economic shift

We’ve seen this exact mechanism play out before, in very different contexts.

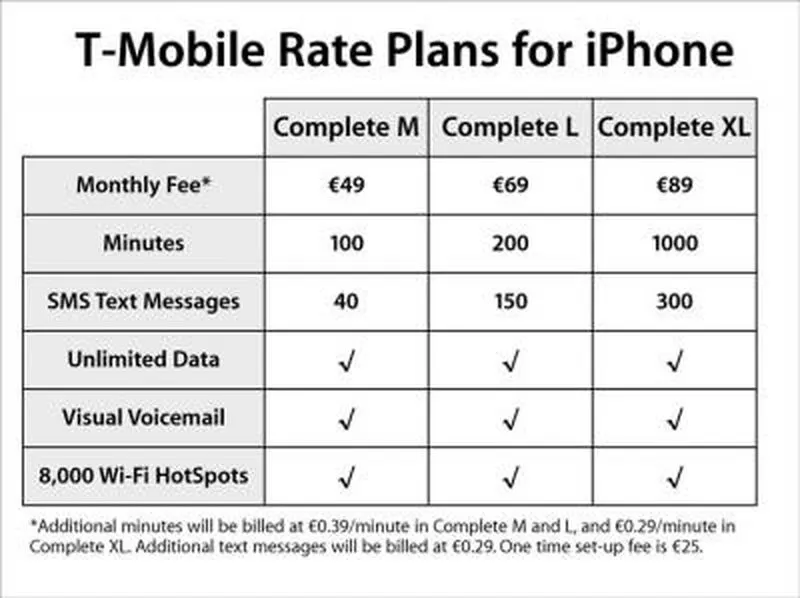

The SMS example is particularly telling.

For years, telecom operators billed messages individually in a tightly regulated and highly concentrated market. Prices were largely aligned, margins were high, and the model seemed unassailable.

Then a simple alternative appeared: free messages over the internet.

The transition was not immediate. Usage habits resisted. Operators tried to defend their model.

But once a sufficiently good alternative existed, with near-zero marginal cost for users, economic pressure did the rest.

Telecom operators did not disappear. Their business model did.

The same dynamic played out in IT infrastructure. On-premise systems were not replaced by Cloud-computing because the Cloud was technically perfect. They were replaced because the Cloud radically changed cost structures, speed and iteration.

This is the pattern AI is now repeating in software production cycles.

Mobile plans of the german telecom company T-Mobile for IPhone in 2007

Mobile plans of the german telecom company T-Mobile for IPhone in 2007

Source: MacRumors

Why this is a matter of life or death

A paradigm shift in production cycles triggers more than technical change.

It forces a reallocation of value.

We move from writing code to designing systems.

From execution to decision-making.

From volume of work to relevance of choices.

When this happens, power dynamics shift.

Some skills lose value.

Others become critical.

Some organizations struggle to adapt.

Others thrive precisely because they move faster and decide better.

This is why production paradigm shifts are never neutral. They act as massive filters.

History is remarkably consistent on this point.

Across major industrial transitions, we observe the same pattern:

- most established players decline or disappear,

- a small fraction successfully adapts,

- new entrants capture a disproportionate share of value over one or two decades.

Not because incumbents are stupid. But because they are optimized for a world that no longer exists.

Orders of magnitude observed in major industrial shifts

The exact numbers vary, but the pattern does not.

- The Industrial Revolution marginalized most traditional workshops.

- Electricity reshuffled industrial leadership built around steam.

- The automobile wiped out horse-based industries within a few decades.

- Digital photography nearly erased analog incumbents.

- E-commerce triggered high mortality among traditional retail chains.

- Streaming dismantled the physical music industry.

In each case, the transition was not instantaneous. But it was irreversible.

The economic reality of our industry

Our industry still largely runs on day-rate billing models.

This model is not inherently bad. But it comes with a structural flaw: time becomes directly correlated with revenue.

Once that incentive exists, a predictable set of behaviors emerges; even without malicious intent:

- vague or elastic scoping,

- scope creep,

- successive justifications for delays or budget increases,

- overruns gradually normalized as “part of the game”.

But it would be naive to assume this is always accidental.

Some actors fully understand this incentive structure and know that a poorly scoped, drawn-out project is mechanically more profitable.

The system protects them.

Complexity makes root causes hard to identify. Responsibilities are diluted. Decisions remain defensible after the fact. Teams rotate before problems become obvious.

Whether driven by incompetence, poor organization or conscious exploitation, the outcome is the same: long projects, rising costs, and value that becomes increasingly hard to measure.

This is not unique to software.

Other expertise-based industries have relied on similar models for decades. Law is a classic example: billing by time in a domain where complexity and uncertainty are inherent, and where regulation is largely shaped by the profession itself.

This is precisely the kind of opacity AI is likely to challenge.

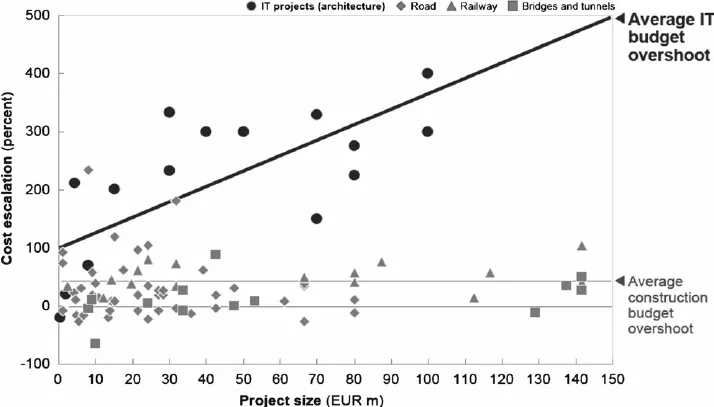

Cost overrun in construction projects and IT projects compared

Cost overrun in construction projects and IT projects compared

Source on ResearchGate: figure 4 in page 363 of Survival of the Unfittest: Why the Worst Infrastructure Gets Built - And What We Can Do About It

Impact on developers

Not all developers are exposed in the same way.

Those who don’t truly understand what they are doing, and mostly produce output without delivering real value, are the most at risk.

Junior developers are also vulnerable, partly through no fault of their own. Graduating is a bit like getting a driver’s license: you’re legally allowed to drive, but you don’t really know how yet.

Senior profiles, on the other hand, are likely to become even more valuable.

Once part of the “writing and maintaining code” effort is absorbed by AI, the hard problems remain:

- understanding what actually needs to be built,

- framing problems and trade-offs,

- steering AI systems,

- diagnosing why something doesn’t work,

- dealing with the unexpected.

In the short term, this will likely reduce the time and energy invested in training juniors. In the medium term, companies will attempt to replicate senior-driven models with less experienced, lower-cost profiles… with mixed results.

The real differentiation will not come from who writes the most code, but from who understands systems, constraints and consequences.

AI as a software feature

Beyond production cycles, AI will increasingly impose itself as a product feature.

Just as smartphones forced software to adapt to touch-based interfaces, most products will eventually need to integrate AI-driven capabilities in one form or another.

This is not a cosmetic change.

It implies architectural shifts, new technical constraints, and entirely new functional and UX challenges. AI systems are probabilistic, stateful, and often hard to reason about.

Designing reliable products on top of them is not trivial.

The real unknown remains scale.

Will the volume of new work created by AI-driven features offset the speed at which production cycles are being compressed?

Honestly, I don’t know.

Impact at my entrepreneurial level

At my scale, a few conclusions are hard to ignore.

Markets will tighten at certain times. Production cycles and service offerings will need to evolve. The economic model itself: day-rate versus fixed-price, must be questioned. The balance between junior and senior profiles will need to be rethought. And company size becomes a strategic variable under uncertainty, not just a growth goal.

A transformation of this magnitude implies risk.

That means scenario planning. Accepting uncertainty. And being ready to activate different paths depending on how fast, and how far, the shift unfolds.

There is, however, a positive side.

These transformations play out over years, not months. They offer time to observe, test, adapt and correct course.

The only truly unacceptable mistake would be to fail to see the change coming and to realize too late that action should have been taken earlier.

And if AI ultimately turns out to be less disruptive than anticipated, the main cost of today’s decisions will be time: experimentation, learning, and adaptation effort.

A non-negligible cost. But a reversible one.

History suggests the opposite mistake is far more dangerous.

Rudy Baer

Founder and CTO of

BearStudio,

Co-founder of

Fork It! Community!

February 12, 2026

AI, Mindset, Business, CTO Sharing